There has been much discussion about New Zealand bats on the CFZ blogs in the last few days. Jon wrote something off-the-cuff about wishing that a certain long-extinct species of New Zealand bat was still in existance. This got me thinking. What was it? Why did it die out? and could it have survived?

New Zealand has been home to three species of bat within living memory. The two species left alive and in a reasonably stable state (well, their numbers have been reduced dramatically, but they are not in danger of extinction yet) are the lesser short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata) and the long-tailed bat (Chalinolobus tuberculatus). But, there was another species, the greater short-tailed bat (Mystacina robusta) which, at 90mm in length was New Zealand’s largest bat. It became extinct in 1967, leaving only one photo of its species taken in 1965. However, it seems someone forgot to tell the bat.

The Short-Tailed Bats are a funny group, being from the family Mystacinidae, and are endemic to New Zealand. The Greater had a large distribution over the northern climes of the island which is known from sub-fossil bones. It was classified as a sub-species of M. tuberculata until 1962 when it left the other 3 sub-species of M. tuberculata to form its own species. Greaters did the job of small rodents on the island, moving on the floor with all four limbs and only flying when necessary. Lessers are slow flyers, rarely getting above 3 meters above the ground, so it is expected that Greaters, with their larger body size, could only live in the north where the temperatures were high enough to allow them to warm up and fly (all Mystacina bats allow their core body temperature to drop at night, so when they want to become active again they need to become hot). Below is the only photo of the greater short tailed bat.

Now here we have an interesting example of an animal going against Bergmann’s Rule (within a group of closely related animals with a large north-south range, species/sub-species nearer the poles are larger). This rule works for “normal” homeotherms (constant body temperature), but here the advantage of keeping the core temperature high by having a large body to retain heat (lower surface area to volume ratio – better heat conservation) is outweighed by the time it takes for the body to heat up again in the day; thus we have small bats nearer the pole, and larger bats further toward the equator.

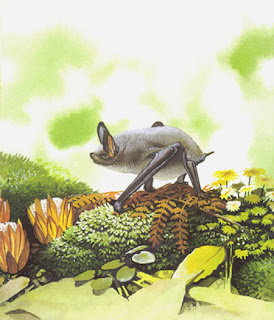

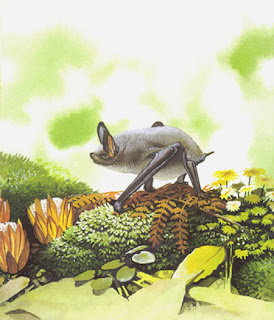

I expect you are now thinking “How on earth did this bat keep its wings out of the way whilst it foraged?”. Very good question: both species did so by tucking the wing membranes under a different membrane on their body, leaving the bats to scurry around in and out of burrows and about on the forest floor as eagerly as a mouse. The illustration shown opposite shows the bat as it would probably have stood, with its wing folded out of the way. They were most likely insectivores like M. tuberculata, but this is not known for certain.

I expect you are now thinking “How on earth did this bat keep its wings out of the way whilst it foraged?”. Very good question: both species did so by tucking the wing membranes under a different membrane on their body, leaving the bats to scurry around in and out of burrows and about on the forest floor as eagerly as a mouse. The illustration shown opposite shows the bat as it would probably have stood, with its wing folded out of the way. They were most likely insectivores like M. tuberculata, but this is not known for certain.

So, why on earth are they gone? Well, New Zealand is one of the countries hardest hit by human intervention, and when rats were introduced to the mainland the short tails were in danger. Habitat destruction began their decline, and very soon rats followed and decimated the local wildlife. Soon, the greater short tail was gone from the main land, surviving only on Big South Cape Island. Then, tragically, rats got to the island from a ship. The populations of South Island saddlebacked wattlebird, Stead's bush wren, Stewart Island snipe and greater short-tailed bat were all but wiped out within the space of a few years. Only the saddleback was saved and is still alive, the other three unique species were gone for ever.

However, the IUCN continue to list Mystacina robusta as Critically Endangered as apparently “recent, unconfirmed reports of bats from this small island [Big South Cape] and a neighbouring island, however, could be this species”. The current evidence for this apparent survival extends to “several reports of bat sightings from Putauhina, and in 1999 Colin O'Donnell recorded Mystacina-like echolocation calls from the island that do not belong to M. tuberculata (O'Donnell 1999). There have also been two unconfirmed reports of bats being seen on Big South Cape. The identity of the bats being seen still must be confirmed” because it could have been one of the two other species. However, the long-tailed bat lives 50km away, which is probably a little far as it has not been recorded on the island before. It was listed as Extinct in the most resent revision in 1996, before being changed to Critically Endangered in 2008.

I expect you are now thinking “How on earth did this bat keep its wings out of the way whilst it foraged?”. Very good question: both species did so by tucking the wing membranes under a different membrane on their body, leaving the bats to scurry around in and out of burrows and about on the forest floor as eagerly as a mouse. The illustration shown opposite shows the bat as it would probably have stood, with its wing folded out of the way. They were most likely insectivores like M. tuberculata, but this is not known for certain.

I expect you are now thinking “How on earth did this bat keep its wings out of the way whilst it foraged?”. Very good question: both species did so by tucking the wing membranes under a different membrane on their body, leaving the bats to scurry around in and out of burrows and about on the forest floor as eagerly as a mouse. The illustration shown opposite shows the bat as it would probably have stood, with its wing folded out of the way. They were most likely insectivores like M. tuberculata, but this is not known for certain.

You might be interested to know that mystacinids are not unique to New Zealand as used to be thought: fossils have shown that they also lived on Australia.

ReplyDeleteOh really? How old is the group then Darren?

ReplyDeleteIf I may be so bold I'd like to bring your attention to... http://scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2007/04/the_most_terrestrial_of_bats.php

ReplyDeleteAll the best.