Hooray! A new venture for both the CFZ and for its shortest member, myself. Alien animals, as we define them, are animals inhabiting a habitat where they are not native. These can be animals which have been introduced into new areas by human intervention, animals moving along pathways which have been created by human activity, or animals which have expanded their range into an unexpected area through natural process.

During this quick introductory post, I will be having a quick look at examples of alien animals in Britain, discussing our plans for the future, and finally, looking at what you, CFZ members and representatives, but first and foremost naturalists, can do to help our studies.

So first, some examples. New area introductions are numerous and well known.

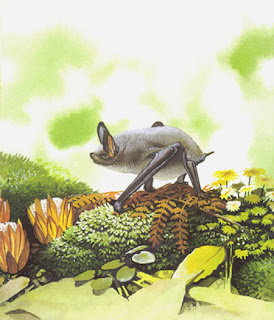

The coypu is a great example. Introduced into fur farms in 1929, this large (4.5-9kg) rodent swiftly made its escape, and soon found that the habitat in East Anglia was very much to its tastes, where it settled and bred very nicely. This news was initially taken as good tidings: Coypu eat a lot of reeds and would clear streams wherever they went, keeping them free flowing. However, it was soon found that they loved vegetables from gardens, and crops from farms, plus their reed clearing activities and burrowing would only cause the river banks to be undermined and collapse. Their only predators big enough to take the babies in Britain were foxes, stoats and herons; they would leave the adults (if only we still had wolves...).

Now, you may be saying to yourself “Well, this is all well and good, but in their native habitat [throughout South America] surely they would cause a huge amount of damage to the area?”. Well, no. Coypu in Britain had hit such densities thanks to so much food from our farms that their numbers could sky rocket. Indeed, some clever ecologist worked out that only when Coypu hit a density of 4 per acre, do they begin to cause large amounts of damage. A huge number of Coypu living in one area of course results in far more burrowing structures than normal, causing bank undermining, and increasing the risk of flood damage.

So, that is new area introductions dealt with, but what about new pathway introductions? This is a bit of an odd term, and I will try to make it clearer. When animals are removed from a food chain, a gap appears which may be suitable for another animal to exploit. For example, by removing top predators like wolves and bears from Britain, we have produced a gap which will be filled by evolution (maybe not now, but certainly in the future, evolution can take a long time to work!). So, by removing these predators, there is a top spot available which is just beginning to be filled by (for the purposes of this article) two types of animal. 1. Big cats, 2. Eagle owls (amongst others)

Big cats, you are quite right, are new area introductions, but they have adapted to new pathways which we have left open. Eagle owls however, may or may not have been present in Britain in recent times before extermination, but they are back! Some birds are undoubtedly captive releases, but some of them I am sure are birds who have flown over from the continent, found a huge amount of prey (from voles to rabbits and even up to buzzards (who incidentally have moving up into that top carnivore slot)) available, so they decided to stay here.

There is currently a male Eagle owl who lives outside the Biology building at Bristol University, which does push this university a little higher up my favourite list for next year. This young fellow is almost certainly a captive release however, but it is still quite interesting! Eagle owls enjoy a bit of a love hate relationship with people, they are stunning birds which people love to see flying around, but when it turns out that they may eat the occasional game bird, the shooting lobby fires up (pun intended) to claim that they should all be shot.

I have nothing against game shooters; indeed, working on a shooting ground has shown me the great help they can be to keeping some species of British bird breeding on land which would have otherwise been eaten up by housing or farmland. The great expanse in breeding areas for game birds must be a good thing, for, as Pink Floyd said, “the price of a few hundred ordinary lives”.

So, that is the basics sorted out. Now for our aims.

We hope to set up a sighting and watch database where we log sightings of alien animals alongside notes about their environment, activity and numbers. We are looking to produce a book by the end of the year: either it will be a monster of a book looking at every alien animal in Britain, from the confirmed to the unconfirmed; or it will be a book split into three parts:

but we shall have to see.

The most important factor in making this venture work is you! The people up and down the country who want to help this project go. You can do so my informing either Jon Downes or myself of any sighting you have of an alien animal, together with as much information as you can get about it (not the animal species itself, but what they are doing there, their size, estimated weight, habits, food source etc), or by suggesting ideas and suggestions to helping this get started. We hope to have you on-board soon.